2024.12.12

コラム/エッセイ「雪の殿様」が生んだ江戸の流行

武部 隆 時事通信ブランドスタジオ社長

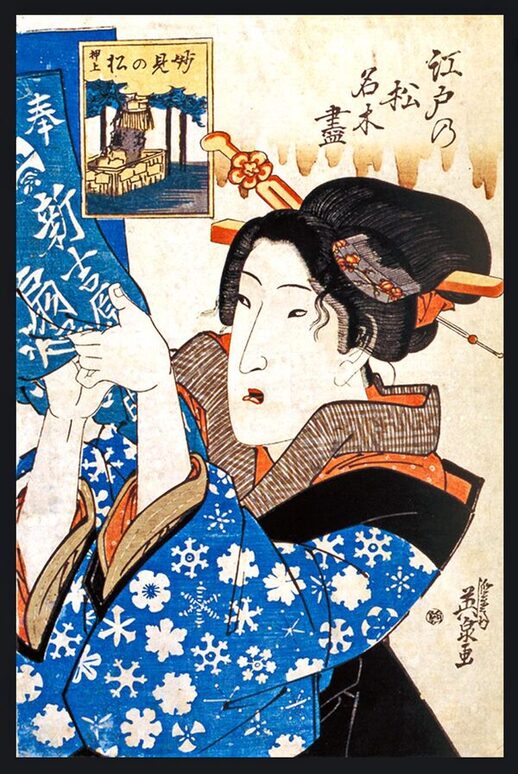

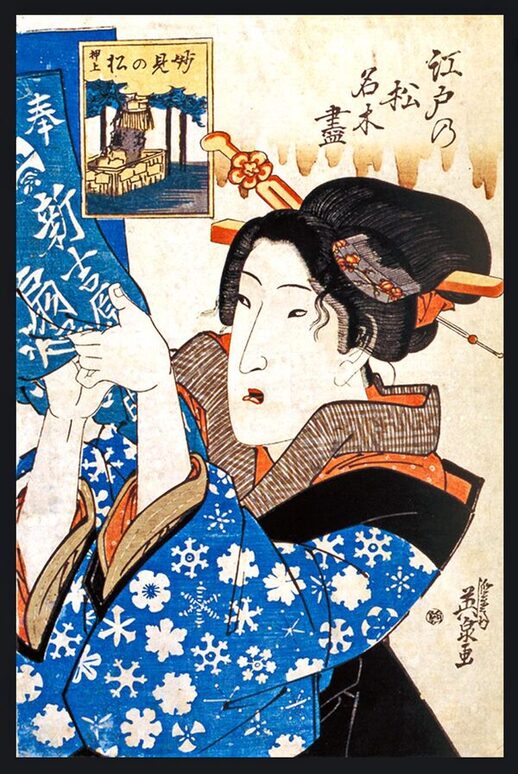

雪華模様の着物が描かれた浮世絵「江戸の松名木尽 押上 妙見の松」

(渓斎英泉作、古河歴史博物館蔵)

「雪華(せっか)」という雪の結晶の文様をご存じでしょうか。名付け親は徳川家に縁のある土井利位(どい・としつら)という殿様です。利位は文政5年(1822)、下総国古河(現在の茨城県古河市)を本領とする古河藩・土井家の11代目当主となりました。土井家は徳川家康の従弟(いとこ)だった利勝を祖とする譜代大名で、利位も奏者番を皮切りに大坂城代、京都所司代と幕府の重職を務め、天保10年(1839)、本丸老中に列しました。天保14年(1843)には、天保の改革に行き詰まって失脚した水野忠邦に替わり、老中首座に任じられています。

利位は幕政を取り仕切る政治家としての能力を発揮する一方、自然科学を探求する博物学者という変わった一面を持っていました。オランダから入手した顕微鏡を使い、空から降る雪の結晶を自ら観察、さまざまな形態の結晶を絵に描いて記録に残したのです。そして、その研究成果を「雪華図説」という解説書にまとめ、天保3年(1832)に刊行しました。雪の結晶の存在を世に知らしめ、それを「雪華」と名付けたのは、博物学者としての利位でした。

雪華図説は私家版として少数しか印刷されず、一般にはほとんど流通しませんでした。ところが、その5年後に江戸でベストセラーとなった博物書「北越雪譜」に雪華図説の雪の結晶図が引用されたことをきっかけに、江戸っ子たちの注目を集めました。

実は、江戸の庶民は現代よりもファッションに敏感でした。江戸時代中期以降、都市の町民が経済力を付け、それまでは武士の特権のようなものだった花見や旅行などの娯楽や行事が庶民にも広まりました。娯楽や行事には「よそゆき」の着物が必要で、そこに江戸っ子の「粋(いき)」を見せたいと誰もが思ったのです。

着物の柄、今で言うテキスタイルパターンは、着る人のセンスが反映されます。その当時、定番とされた棒縞(ぼうじま)、千筋(せんすじ)などのしま模様、弁慶格子(べんけいごうし)、子持格子(こもちごうし)といった格子模様、鮫小紋(さめこもん)、行儀小紋(ぎょうぎこもん)に代表される小紋柄などのパターンには多種多様なアレンジが施され、江戸っ子は着物の柄で粋を競いました。

常に斬新なパターンを追い求めていた江戸の服飾業界は、雪華図説で描かれた雪の結晶に飛び付きました。六角形を基本としながら、決して同じものはできないという結晶の多様性に加え、手に取れば一瞬で溶けてしまう雪のはかなさも、日本人の美意識に突き刺さったに違いありません。天保の江戸を、雪の結晶をモチーフにしたテキスタイルデザイン「雪華模様」が席巻した事実は、当時の浮世絵で雪華模様の着物を着た人物が多く描かれたことでも裏付けられます。

江戸の庶民は、雪の結晶のデザインを世に広めた土井利位に敬意を示すことも忘れませんでした。雪華模様の別名「大炊模様(おおいもよう)」は、利位の官名が「大炊頭(おおいのかみ)」だったことに由来します。かつて土井家が治めた茨城県古河市でも、利位は「雪の殿様」として市民から親しまれ、今も町のあちこちで雪華模様のデザインを見ることができます。

【English version】

Edo Fashion Trend Born of “Snow Lord

Takashi Takebe President, Jiji Press Brand Studio

Ukiyoe “Edo no Matsu Meiki Zetsu Oshiage Myoken no Matsu” (Pine trees and famous trees in Edo, Oshiage Myoken no Matsu) with a kimono with snowflake pattern.

(By Eisen Keisai, owned by the Furukawa Museum of History)

Have you ever heard of the snowflake pattern called “Sekka”? Its godfather was a lord named Toshitatsura Doi, who was related to the Tokugawa family. In 1822, Toshiki became the 11th head of the Doi family of the Furukawa domain, whose main domain was Furukawa in Shimousa Province (present-day Furukawa City, Ibaraki Prefecture). The Doi family was descended from Toshikatsu, a cousin of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and Toshiki held important positions in the shogunate, starting as a Kanadeban, then as a representative of Osaka Castle, and finally as a representative of Kyoto. In 1843, he replaced Tadakuni Mizuno, who had lost his post after the Tempo reforms stalled.

While Toshinori demonstrated his ability as a politician in charge of the shogunate, he also had an unusual aspect: he was a naturalist who explored the natural sciences. Using a microscope he acquired from the Netherlands, he observed snow crystals falling from the sky, and drew pictures of the various forms of crystals to record his findings. He then compiled the results of his research into a commentary entitled “Illustrated Description of Snow Crystals,” which was published in 1832. It was Ritsui, as a naturalist, who made the existence of snow crystals known to the world and named them “sekka” (snowflakes).

Seikka Zusetsu was printed in a small number as a private edition and was rarely circulated to the general public. However, five years later, the snow crystal illustrations from the Yukika Zusetsu were quoted in the best-selling natural history book “Hokuetsu Yukifu,” which attracted the attention of the Edo people.

In fact, the common people of Edo were more sensitive to fashion than today. From the mid-Edo period onward, urban townspeople gained economic power, and entertainment and events such as cherry blossom viewing and travel, which had previously been the privilege of the samurai, became popular among the common people. For entertainment and events, “outing” kimonos were necessary, and everyone wanted to show the “iki” (iki) of the Edo people.

Kimono patterns, or textile patterns as they are called today, reflect the sense of the wearer. The standard patterns of the time, such as striped patterns like Bo-jima and Sen-suji, plaid patterns like Benkei-goushi and Komochi-goushi, and komon patterns represented by Same-komon and Gyogi-komon, were arranged in a wide variety of ways, and the Edo The Edo children competed with each other in kimono patterns.

The Edo clothing industry, which was always in pursuit of novel patterns, jumped on the snowflakes depicted in the Yukika Zusetsu. In addition to the diversity of crystals, which are based on hexagons but are never identical, the transience of snow, which melts in an instant when picked up, must have struck a chord with Japanese people's sense of beauty. The fact that textile designs using snowflakes as motifs, known as “Yukikamon,” swept through Edo during the Tempo period (1600-1868) is supported by the many depictions of people wearing Yukikamon kimonos in ukiyoe prints of the time.

The common people of Edo also did not forget to show their respect to Doi Toshinori, who introduced the snowflake design to the world. The name “Oimoyo,” also known as the snowflake pattern, derives from the fact that Toshikazu's official name was “Oimokami,” which means “head of the Oimono” (the head of the Oimono family). In Koga City, Ibaraki Prefecture, where the Doi family once ruled, Toshinori was known as “Lord of Snow” by the citizens, and the Yukika pattern can still be seen here and there in the city.

カテゴリー: コラム/エッセイ

関連タグ: #文様