2025.08.28

白洲信哉の「多様なるジャパン」「多様なるジャパン」 第10回 辻が花

白洲信哉=文筆家、日本伝統文化検定協会副会長

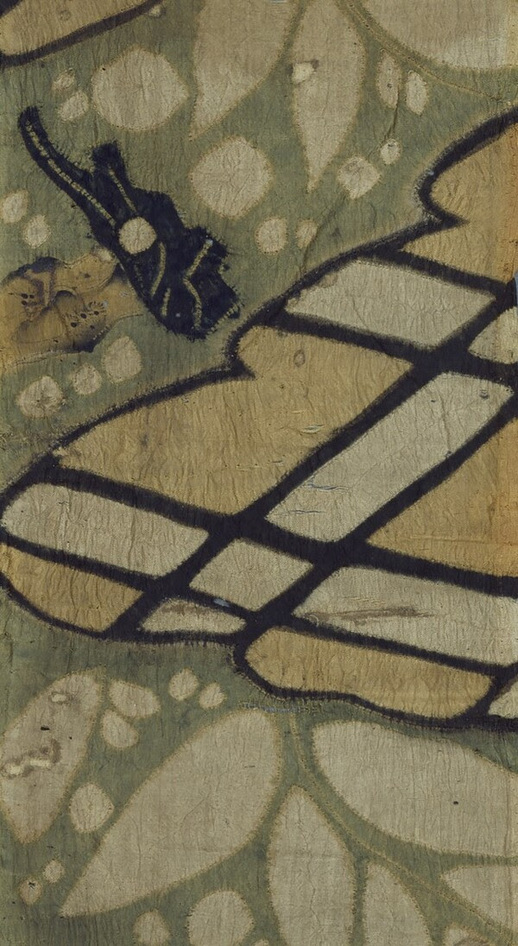

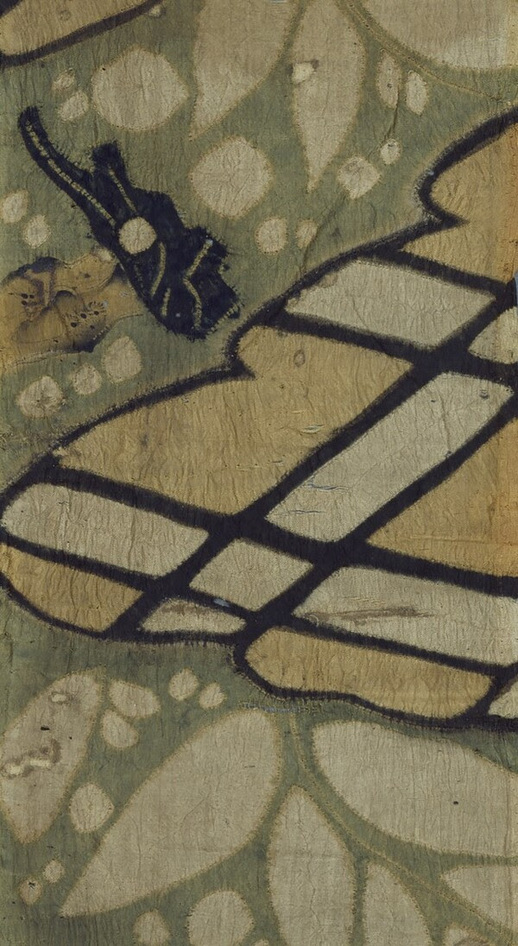

染織裂 染分練貫地雲取り桐木瓜文様辻が花染裂

出典:ColBase(httpscolbase.nich.go.jp)を加工して作成

前回「藍染」と付けたが、「辻が花」もジャンルなら同じ染織物になるようだ。だが、明治以降、絵画に彫刻、工芸などジャンルを縦割りにしてしまったため、各分野の硬直化を招いてしまったように思う。例えば第5回で書いた「根来」の朱色は、漆にベンガラや水銀朱を混ぜたように、漆を緑色に発色させるには、藍染の精製過程で生じる藍華を混ぜるとうまく緑色に発色するという。つまり、技術革新とは時代の要請と異分野がコラボして生まれるわけで、工芸に限らず、どの産業にも通じる硬直化はわが国の大問題だと僕は思う。

さて、伝検テキストに「辻が花」は掲載されていない。技法的には絞り染を基調に摺箔(すりはく)に刺繍(しゅう)や描き絵を併用したもので、最も古い出典は、「三十二番職人歌合(うたあわせ)」に描かれた桂女(かつらめ)が身につけた小袖(桂包)の詞書きに「つしか(辻が)花を折る」とあり、14世紀末朝廷から特別な庇護(ひご)を受けた公家衣装であった。やがて時代は武士の台頭とともに身分格差が縮まり、上洛した信長が見たものは、応仁の乱から復興しつつあった華やかな街の姿と、キリスト教という華やかな南蛮文化だった。続く秀吉は信長以上に、例えば豪華絢爛(けんらん)なペルシャ絨毯(じゅうたん)を切って陣羽織に仕立てる。やがてモードは町衆や庶民にも広まり、今日の呉服屋である「小袖屋」が出現する。巨大な富を集めた新興勢力は、着飾る楽しさを満喫、僕の好きな桃山バサラ時代に「辻が花」は最盛期を迎えるのである。

意匠は時代を映す「鏡」というが、辻が花を一口で説明するのは困難だ。なぜなら辻が花の発展形という友禅のように一個の独立した染技法ではなく、小袖の加飾手段として絞りが中心ではあるが、時々の模様表現が技法による制約を受けず「当意即妙」に、先のような刺繍や摺箔など多様な技法も採用したからである。僕が感じるのは同時代の美濃焼の織部に通じる自由闊達(かったつ)なデザインだ。絵模様や造形が即興的なように、絞り染の上に椿や藤の花が描かれたかと思うと、突如として関係のない格子や市松模様が現れたりする。かといって全体の調和を乱すことなくバランスがとられているのである。

わが国の生活は自然と離れては成立しない。春には春の花をあしらい、寒いときには織りが厚いものを、そして夏には涼しげな薄い配色を纏(まと)う。不易に対するモードは時代の先駆者が作り、武将が鎧(よろい)の上から羽織る胴服にもその手法が使われるなど、中世的な束縛から放たれ、型にはまらない溌剌(はつらつ)とした「美」を創造したが、辻が花や織部のように風の如(ごと)く消えてなくなっていったのだ。

【English version】

‘Diverse Japan’ Part 10: Tsujigahana

Shirasu Shinya = Writer, Vice-Chairman of the Japan Traditional Culture Testing Association

Dyed and woven fabric fragment

Dyed, blended, and polished ground with cloud-patterned paulownia and quince motifs

Tsujigahana-dyed fabric fragment

Source: Created by processing data from ColBase (httpscolbase.nich.go.jp)

Last time I referred to it as “indigo dyeing”, but “Tsujigahana” also appears to be a type of dyed textile within the same genre. However, since the Meiji period, the vertical division of genres into painting, sculpture, crafts, and so forth seems to have led to rigidity within each field. For instance, the vermilion of ‘Negoro’ mentioned in the fifth instalment, which is produced by mixing lacquer with bengara or mercury vermilion, similarly requires adding indigo flowers a byproduct of the indigo dyeing refinement process to achieve a successful green hue in lacquer. This illustrates that technological innovation arises from the demands of the era and collaboration across different fields. I believe this rigidity, not limited to crafts but prevalent across all industries, is a major issue for our nation.

Now, Tsujigahana is not listed in the traditional craft examination texts. Technically, it is based on shibori dyeing, combined with surihaku (gold leaf rubbing), embroidery, and painted designs. The earliest known reference is in the ‘Thirty-Two Craftsmen Poetry Contest’, where the verse accompanying the kosode (Katsura-tsutsumi) worn by Katsura-me reads ‘plucking tsushika(tsujiga)-hana’. It was court attire receiving special patronage from the imperial court in the late 14th century. As the era progressed and samurai rose to prominence, class distinctions narrowed. What Nobunaga witnessed upon entering Kyoto was the resplendent city recovering from the ohnin War, alongside the dazzling Nanban culture of Christianity. Hideyoshi, succeeding him, surpassed Nobunaga in extravagance, for instance cutting sumptuous Persian carpets to make his battle robes. Fashion soon spread to townspeople and commoners, giving rise to the “kosode shops” that became today's kimono merchants. This emerging power, amassing immense wealth, revelled in the pleasure of dressing up. It was during my beloved Momoyama Basara period that Tsujigahana reached its zenith.

Designs are said to be a “mirror” reflecting their era, yet Tsujigahana is difficult to explain succinctly. This is because, unlike yuzen its evolved form,Tsujigahana was not an independent dyeing technique. Centred on shibori as a means to decorate kosode, its occasional pattern expressions were unconstrained by technique, employing diverse methods like embroidery and surihaku as described earlier, all executed with “immediate ingenuity”. What strikes me is a free-spirited design sensibility akin to that of contemporary Mino ware's Oribe ware. Just as the painted patterns and forms seem improvisational, one might find camellia or wisteria blossoms depicted atop shibori dyeing, only for unrelated grid or checkerboard patterns to suddenly appear. Yet, this never disrupts the overall harmony; the balance remains intact.

Life in our country cannot exist divorced from nature. In spring, we adorn ourselves with spring flowers; in cold weather, we wear thickly woven fabrics; and in summer, we drape ourselves in cool, light colour schemes. The mode for the timeless was created by the pioneers of the age. This technique was even employed in the tunics worn over armour by warlords, liberating them from medieval constraints and creating a vibrant “beauty” unconstrained by convention. Yet, like Tsujigahana and Oribe, it vanished as swiftly as the wind.

カテゴリー: 白洲信哉の「多様なるジャパン」

関連タグ: #染織